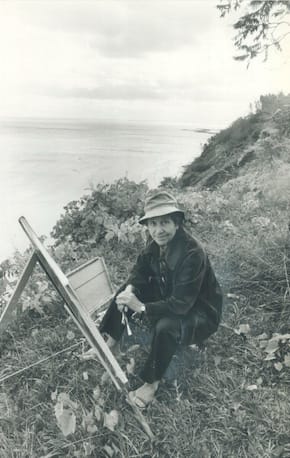

From the very beginning, McCarthy was on the move. Even in her first three years, she carried a restless energy that friends and family would later describe as unstoppable. Travel, exploration, and curiosity came naturally to her. Her father, George, shared a deep love of the outdoors, and summer after summer, he brought the family to cottages on Lake Ontario or the northern lakes around Toronto. McCarthy remembered, “Dad had conditioned me to feel that nature and the out-of-doors were an important part of my heritage.” In 1926, George bought a weathered cottage near Beaumaris on Lake Muskoka. Together, father and daughter repaired the roof and tended to the property, a hands-on education that foreshadowed the time McCarthy would later spend building her own home on the Scarborough Bluffs.

Doris McCarthy’s mother first called her plot of land “Fool’s Paradise” as a kind of teasing warning. When Doris bought the undeveloped property on the edge of the Scarborough Bluffs in 1939, it was remote, windswept, rugged, overgrown, and without any utilities, no road, no water, and certainly no comfort.

Her mother thought the 12 acres of land overlooking Lake Ontario was an impractical, even foolish dream for a young woman to take on such a challenge alone. Instead of being insulted, Doris embraced the name. She saw the irony and humour in it, and “Fool’s Paradise” became a perfect reflection of her philosophy, the joy of living freely, following one’s passions, and finding wisdom in what others might call folly.

Over the decades, she built her home there almost entirely by hand, using reclaimed materials and her own carpentry skills. The site included her residence, studio, and the surrounding natural landscape that inspired so much of her later work.

Faith was a quiet but persistent presence in Doris McCarthy’s life, a shared bond between mother and daughter that grounded her even as she wandered into the farthest corners of the natural world. Her mother, by contrast, was a more complicated figure—a source of both tension and inspiration. Despite disagreements over how women should live and behave, she supported Doris’s artistic ambitions at every turn. Doris inherited her mother’s stubborn streak, along with a deep sense of loyalty. “I think she looked back wistfully… at the opportunity she had missed, and I’m sure that was one of the reasons she supported me in every effort… to become an artist,” McCarthy reflected.

Doris McCarthy’s artistic lineage connected her to some of Canada’s most important art movements. As a young student at the Ontario College of Art, she was taught by members of the Group of Seven, including Arthur Lismer and J.E.H. MacDonald, and by John Beatty, whose lyrical interpretations of the northern landscape deeply influenced her sense of form and atmosphere. Their teachings grounded McCarthy’s early understanding of structure, colour, and the moral force of the Canadian wilderness, a theme she would explore throughout her long career. Later, as an art educator herself at Central Technical School, McCarthy inspired a new generation of artists, including Kazuo Nakamura of Painters Eleven, who would carry forward her insistence on disciplined craft and spiritual engagement with nature. Her classroom became a crucible of Canadian creativity, where the ideals of the Group of Seven evolved into a more modern language. In this way, McCarthy stood at a remarkable intersection of Canadian art history, shaped by its early masters and shaping those who would redefine it.

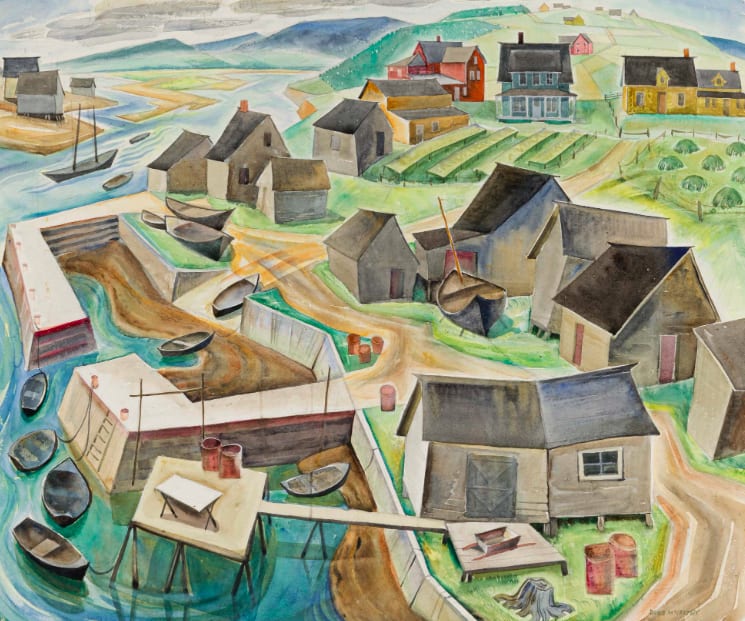

The Complete Barachois, a Panoramic View of the Fishing Village, Gaspé, 1954, watercolour on paper

by Doris McCarthy

Doris McCarthy’s career was defined by both her artistic innovation and the widespread recognition she earned across Canada. In the mid-1960s, she faced professional challenges at Central Technical School when Virginia Luz was promoted over her, yet McCarthy persisted and by 1969 was appointed assistant head of the art department, which brought new responsibilities and greater satisfaction in her final years at the school. In 1964, she broke new ground as the first woman elected president of the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA), guiding the organization through a period of financial strain and institutional change, while also lending her voice as a defence witness in the 1965 trial surrounding Dorothy Cameron’s controversial Eros ’65 exhibition. At the same time, she engaged the public through her weekly radio program, OSA on the Air, and explored a distinctive hard-edge approach to landscape painting, producing works like Georgian Bay from the Air, (1966), that balanced abstraction and representation with clarity and calm.

Georgian Bay from the Air (1966), oil on masonite, 24 x 30 inches

by Doris McCarthy

Her reputation among collectors and galleries expanded rapidly. A significant exhibition organized by Laszlo Reichel at the Gutenberg Gallery, which featured around forty of her works, sold out entirely, confirming a strong demand for her paintings. In 1973, McCarthy achieved another milestone by becoming a full member of The Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, submitting her Iceberg Fantasy before Bylot as her diploma piece.

Her Iceberg Fantasy series comprises over sixty paintings that she developed after her initial visit to the Canadian Arctic in 1972. The works are imaginative interpretations of icebergs, blending abstraction with elements of realism. McCarthy employed thin washes of blues and whites to convey an ethereal translucence, capturing the interplay of light and form in these icy landscapes dorismccarthygallery.utoronto.ca+1.

Iceberg Fantasy Bylot, 1974, oil on canvas, 30 x 48 inches

by Doris McCarthy

She later established a lifelong partnership with the Wynick/Tuck Gallery, who represented her with great success. Her contributions also extended to civic projects, such as her abstract design for the Scarborough city flag, and her visibility grew internationally through the documentary Doris McCarthy: Heart of a Painter (1983).

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, McCarthy’s achievements continued to accumulate. She received the Order of Canada in 1986, an honor initiated by a nomination from former student Joyce Wieland, and later the Order of Ontario.

Receiving the Order of Canada in 1986

Major retrospectives, including Doris McCarthy: Feast of Incarnation, Paintings 1929–1989 (1991), toured multiple galleries in Ontario and Quebec, while her autobiography series chronicled her life and work. Scarborough recognized her contributions by proclaiming June 4, 1996, as “Doris McCarthy Day.”

Consignment at Rookleys

At Rookleys Canadian Art, we are actively seeking works by Doris McCarthy for consignment, offering consignment rates far lower below what auction houses charge. If you have a painting by Doris McCarthy to consign, please contact us at info@rookleys.com to discuss these opportunities further.

Okanagan Valley Near Osoyoos, B.C., 1989, oil on canvas

Okanagan Valley Near Osoyoos, B.C., 1989, oil on canvas

by Doris McCarthy